Understanding the Drainage Systems in India:

India’s varied land and climate support one of the most detailed drainage networks found worldwide. Ages of movement, rain and wind have turned these rivers and streams into essential life sources for the Indian subcontinent. They help farms, industries, clean drinking water and nature. In India, because its terrain stretches from massive mountains to wide plains and rugged plateaus, drainage patterns vary from region to region.

Drainage Systems in India are classified.

Most drainage systems in India fall into one of two categories: Himalayan drainage and peninsular drainage. Both systems come from different origin points, are different ages, have different topographies and have their own hydrologic characters.

Himalayan rivers are always flowing because they are fed by both melting snow and glaciers and rain brought on by monsoons. The mentioned rivers are the Ganga, Yamuna, Indus and Brahmaputra. These rivers are young, active and recognized for having variable paths, steep gorges and fertile floodplains. About 500 million people in India rely on the Ganga River which flows for over 2,525 kilometres and covers 861,000 square kilometres. As the Brahmaputra moves for about 2,900 kilometres from Tibet to Bangladesh, the huge amount of sediment in its waters frequently causes flooding in Assam.

The rivers of the Peninsula, however, are much older than the rest. They run on strong and stable rock across the Deccan Plateau and mainly depend on rainfall, so rivers tend to flow more heavily at different times of the year. The Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery and Mahanadi are the main rivers in India. With a length of 1,465 kilometres, the Godavari which is sometimes called the Dakshin Ganga, is the longest river on the Indian peninsula and empties into a basin measuring more than 312,800 square kilometres. Since they move in a straighter way and usually don’t flood, they work best in an area with fewer rainy days. However, they can dry off during extended dry weather.

Drainage shand shapes

The arrangement of drainage features in any place is a sign of the rocks underneath and the local geology. India has a large area where the dendritic pattern dominates, found in the northern plains and on the Deccan Plateau. Rivers like those in the Amarkantak and Western Ghats flow out from a main peak in radial fashion. Aravallis and Vindhyas, for example, have been folded into shapes forming trellis and rectangular patterns.

Rivers in this region form steep valleys and transport a lot of sediment, thanks to their strong slope and being fed from glaciers. These rivers in the peninsula areas are older, run through well-cut valleys and plains and have smaller sediment loads than those in the larger drains. Indian drainage patterns are made complex and continually changing by the influence of tectonic uplift, different climates and monsoonal changes.

Inland Drainage and Arid Basins

In India, most areas with inland drainage lie in arid and semi-arid lands, since rivers finish in lakes, salt flats or dry pits instead of reaching the sea. These regions comprise approximately 10% of the nation’s land and Rajasthan, Gujarat and Ladakh are the largest within them. Within the 200,000 square kilometres of the Thar Desert, many temporary streams simply enter the sands and dissolve. The Sambhar Lake in India is among the biggest drainage systems, occupying more than 230 square kilometres and its main function is salt production. Another substantial inland basin, the Rann of Kutch, gets water from the Luni River, the only important river there.

Pangong Lake and Tso Moriri in Ladakh belong to basins that do not discharge into any ocean, called endorheic basins. As water in inland drainage basins evaporates quickly, water sources shrink and the chances of desertification rise. Research shows that climate change and human practises have caused over 60% of Rajasthan’s water bodies to lose water. For these zones to support life, people mostly depend on drawing groundwater and collecting rain.

One result of the Aravalli Range is that rivers like the Banas River drain away from the ocean, filling up inland basins where they end. These areas deal with both a lack of water and desertification which is why sustainably managing water supply matters a lot. Natural water shortages caused by inland drainage are fought through projects such as rainwater harvesting, groundwater replenishment and water conservation.

Managing water resources and conserving nature in India’s dry areas depend on understanding inland drainage. Basin studies play an important role in planning irrigation, protecting water resources and guiding sustainable projects in places with less water.

Indian agriculture depends on rivers which provide irrigation for many farmers. Over 20 big river basins are found in India and the most important for agriculture are the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, Godavari, Krishna and Cauvery. Around 78% to 90% of the freshwater in India is allocated to agriculture, so it falls on rivers to maintain food production. Within the 1.08 million square kilometres of the Ganges Basin, over 400 million people are sustained by the area’s fertile plains which provide wheat, rice and sugarcane. Likewise, the Indus River system which is shared with Pakistan, waters more than 26 million hectares of agriculture, making it one of the biggest irrigation networks on the planet.

River-fed watering makes up a big part of India's agriculture and about half of the land cultivated is currently irrigated, hoping to reach 75% to meet the growing challenges from climate change. But poor water use and the excessive removal of groundwater cause problems. Many studies show that rice and sugarcane use almost 60% of the country’s irrigation water which is cause for concern about the future. Examples of such initiatives are micro-irrigation, the development of watersheds and recharging underground water supplies. In addition, Pani Bachao, Paisa Kamao in Punjab rewards farmers who use less water on their land.

In addition to irrigating land, rivers provide fish for food and water supplies, power for factories and nutrients for the soil needed by those who depend on agriculture. The floods of the Brahmaputra River fill the area with silt, making soil in Assam and West Bengal much more fertile. Even so, disturbances such as climate change and pollution Impact Rivers which impacts the harvest farmers gather. Ensuring agriculture is sustainable and productive over time depends largely on solving water problems with rainwater harvesting and efficient watering. To stay food-secure and stable economically, India will need to manage river water efficiently as it works toward climate-resilient farming.

Urban Drainage and Flooding Issues

India faces major flooding problems in cities because of fast city growth, problems with drainage and climate change. Frequent severe flooding in Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru and Delhi leads to lost lives and costly economical consequences. Urban spaces have a lot of concrete and asphalt, reducing their ability to take in water. This causes water to flow away in large groups and leaves some districts with pools of water. Experts report that in cities, flood peaks are at least 1.8 times higher and at most go up by a factor of eight compared to rural areas.

A big reason for this is the broken or poorly maintained storm water systems, as old drains become clogged by solid waste. In addition, about half of water sites in cities like Chennai and Bengaluru have faced encroachment which disrupts the city’s natural drainage mechanisms. In the past decade, extreme rainfall in India rose by 67%, due to the impact of climate change. It can lead to damage to buildings and roads that costs over ₹10,000 crore each year and to the spread of diseases like cholera and dengue.

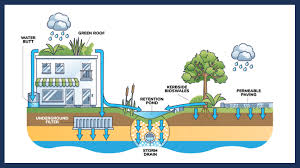

URBANISATION WORK The Smart Cities Mission, AMRUT and Jal Shakti Abhiyan were launched by the government to better manage drainage in cities and make them ready for floods. The crisis can be managed better with more use of permeable paving, rainwater harvesting, improving waste management and better drainage systems. Strong urban environments in India need policies, public awareness and new technology to manage urban flooding.

1. Bengaluru faces problems with drainage.

Although Bengaluru was called the "City of Lakes" in the past, recent urbanisation and unsuitable drainage planning have caused it to flood badly. Over the years, excess rainfall was dealt with in the city by using a linked system of lakes and stormwater drains (rajakaluves). Still, more than half of its

lakes are being encroached, resulting in repeated waterlogging. Some experts think that the irrigation methods created by the Maharajas worked better, because they adapted to the land instead of trying to change it. Because today’s unrestrained growth covers the natural waterways with concrete, Bengaluru faces the risk of flooding.

2. Chennai’s 2015 flood disaster

November and December 2015 were disastrous for Chennai, as 494 mm of rain within just 24 hours caused the city’s drainage to fail. Because parts of the Adyar and Cooum rivers were used, water flow was stopped and the flood was made worse. More than ₹15,000 crore in damage and countless displaced people were reported after the cyclone. Specialists believe that by restoring lakes and fixing storm water drainage, these kinds of emergencies can be stopped in the future.

3. Expanding Development in Bhubaneswar and Limits to Off-The-Plain Flood Defence

Experts found that the percentage of paved surfaces in Bhubaneswar jumped from 51.28% to 81.12%, meaning much less water is being absorbed by the city. Experts believe the intensity of rain will keep rising which makes floods more likely. Because the city’s sewers can’t keep up with development, many low-lying places experience frequent flooding.

4. Mumbai’s experience with monsoon floods

Poor drainage and too much construction cause Mumbai to flood every year. Once, the Mithi River helped the city by draining rainwater, but now its capacity for drainage is greatly reduced by development around it. A drainage system installed a century ago cannot handle the amount of rain that falls today, resulting in big problems with transportation and normal life.

What I suggest moving forward

- Rehabilitating natural ways for water to flow by improving lakes and wetlands.

- Replacing or repairing infrastructure that drains storm water to deal with heavy rain.

- Building into cities by making roads and covering spaces with materials that allow rainwater to flow through.

- A tight ban in place for the tampering of water bodies and drainage channels.

Water Pollution and River Health

India’s rivers are facing an ecological crisis. Pollution from domestic sewage, industrial effluents, and agricultural runoff has rendered large stretches of rivers unfit for human use. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) reported that over 275 rivers in India are polluted, with the Ganga and Yamuna among the most affected. The Ganga, despite several clean-up campaigns, continues to receive over 3 billion litters of untreated sewage every day.

Apart from sewage, rivers are contaminated by heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, and micro plastics. In Varanasi and Kanpur, the Ganga has high levels of chromium and lead due to tannery and industrial waste. In Gujarat, the Sabarmati River suffers from dye and chemical discharge from textile industries.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has issued numerous directives to control river pollution, but enforcement remains weak. A 2021 study by NITI Aayog found that 70% of India’s surface water is contaminated, contributing to more than 200,000 deaths annually due to waterborne diseases.

Community-based river clean-up initiatives have gained traction. In Pune, the Mula-Mutha River Restoration Project is integrating public participation and green technology. In Kerala, the Haritha Keralam program has cleaned and revived several small rivers and canals.

Testing Challenges Over Shared Rivers

Many water disputes between Indian states have arisen due to the national government’s federal system and sharing of river water. The argument over Cauvery water between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu has raged since the 19th century. Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have had several tribunal interventions in the dispute about the Krishna River. When droughts occur, these disputes usually lead to protests, court cases and a disturbance in social peace.

Main conflicts besides the dam ones are those involving the Mahanadi between Odisha and Chhattisgarh and the Yamuna between Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh. Slow decisions from tribunals, unenforcement of verdicts and political intervention stop the process.

We need a legal system that makes water sharing work properly and abide by certain rules. The 1956 act on Inter-State River Water Disputes has been altered a number of times, yet people keep complaining about slow formation of tribunals and enforcing the decisions.

Actions and Policies Made by Authorities

Many new, ambitious programmes have been launched by the Indian Government to refresh and protect its river systems. In 2014, the Namami Gange Mission began with a budget of more than ₹20,000 crore, working on processes like sewage treatment, making river surfaces tidy, sanitation in rural areas and educating the public. Even though more than 150 sewage plants have been set up, the extent of the pollution requires steady actions and teamwork by different states.

The main purpose of the National River Linking Project (NRLP) is to connect water from heavily supplied rivers to areas that are in need. If carried out, the project would involve 30 rivers and cost 5.6 lakh crore rupees. Critics say that climate change could lead to major ecological problems, relocate large populations and bring doubt to hydrological predictions.

Besides, the National Water Policy (2012) encourages using all available water wisely and the Atal Bhujal Yojana looks after groundwater management issues.

In urban areas, AMRUT and Smart Cities Mission seek to bring modern drainage to cities, but the scheme works differently in each state. In India’s countryside, Jal Shakti Abhiyan and Mission Kakatiya (in Telangana) work to restore traditional water bodies and improve how watersheds are managed.

Technology and How the Community Helps

Recent inventions such as GIS, remote sensing and artificial intelligence, are changing the way people plan water resources. As a result, cultures can now observe river health in real time, predict floods and model entire river basins. Together, the Central Water Commission and ISRO have introduced various projects to apply information from satellites to better care for river basins.

https://www.profitableratecpm.com/dnn2ihpxmf?key=3650631fea186f9e482ec854ee81cb45

Creating mobile apps for reporting on river condition, collecting concerns from people and receiving citizen science work is becoming possible. The Ganga Rejuvenation app gives people the chance to photograph polluted locations and get involved in public awareness efforts.

Involving the community is just as necessary. Throughout India, local organisations and NGOs are helping to clean rivers, restore lakes and enlighten people about conservation. For example, in Maharashtra the Ralegan Siddhi model has been created by citizens and the Kumudvathi River has been revived in Karnataka thanks to community action.

To make river conservation more meaningful, school programmes, river festivals and involvement campaigns such as “Arth Ganga” are now including social and cultural elements.

Survival and prosperity in India depend on the country’s drainage systems. They have influenced societies, helped farming, protected diversity of life and supported the economy. Still, pressure from a growing population, more industry, more pollution and climate change is causing difficulties for their sustainability. India must use an all-basin strategy that helps both the development and protection of ecosystems. Taking bold actions, encouraging technology use, cooperating with other states and participating as a community can support India’s rivers supplying life-sustaining resources for future generations.

By studying India’s drainage systems in depth, we identify their necessary roles in each area from the physical to the socio-political, economic and environmental. Handling these various challenges requires leaders, commitment and teamwork.

Rivers in India will be wholly protected in the future if we regularly check and record data on waterways, adapt our strategies and value water as something all Indians can rely on and use together.

No comments:

Post a Comment